Posts tagged: Articles

New Paper: A review on Brain Gene Expression and Behaviour

I am very happy to announce the recent publication of a collaborative review on the relationship between brain gene expression and behaviour with Dr. Gene Robinson at the University of Illinois. We reviewed a large number of studies examining changes in brain gene expression in the honey bee across a wide spectrum of behaviours, environments, and honey bee subspecies.

We showed that brain gene expression is intimately linked to behaviour and that changes in brain gene expression bring about changes in behaviour. We discuss how changes in the environment as well as changes in physiology affect bee behaviour by first affecting brain gene expression. Finally, we showed that the association between specific genes and behaviour can be highly conserved over evolutionary time, leading to common basis of behaviour across distantly related animals.

The review appeared last week in Annual Review of Genetics

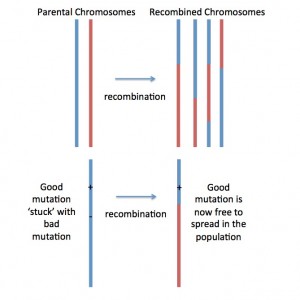

New Paper: Recombination and Honey bee evolution

Fig. 1. Recombination shuffles ‘parental chromosomes’ (red and blue), generating ‘mosaic’ or recombined chromosomes. This is how recombination makes natural selection act more effectively: Lets imagine a new beneficial mutation occurring nearby a deleterious (=bad) mutation on the blue chromosome. With no (or low) recombination, the two mutations would be stuck together… forever… and this would prevent natural selection from removing the bad mutation and spreading the good mutation. But if recombination generates a new mosaic chromosome that has the good mutation but not the bad mutation (as pictured), then the good mutation can spread by natural selection!

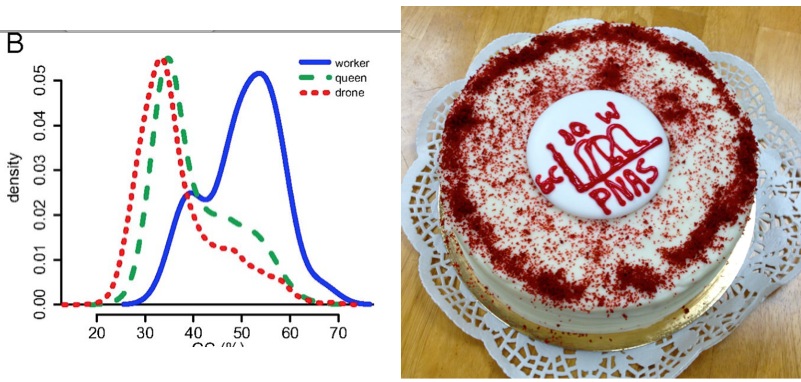

Worker ‘genes’ are GC rich baby! Fig 2 from our PNAS paper, in both tiff and cake formats. The Tiff format is more impactful but the cake format is tastier

So, our results show that the bee’s high recombination rate increases the evolutionary rate of genes associated with worker behaviour, which is an important finding because worker behaviour plays a major role in determining the fitness of insect colonies.

The paper was authored by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Clement Kent, and former Masters students Shermineh Minaei and Brock Harpur.

[edit March 2013]. See Faculty of 1000 recombination, comment by Hunt et al and our reply, and addendum in Communicative and Integrative Biology

PNAS Cake

Today was a fine day. We had a very important paper from the lab accepted in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), one of the top journals in our field. I can’t tell you much about the work for now – it is embargoed until officially published by the journal – other than… it is very very very cool! But, perhaps you can guess the topic after seeing our ‘PNAS Cake”! [feel free to send your guesses via the comment box below]

The cake-lady at highland farms had a good chuckle when i handed her fig. 2 of our manuscript at 8:45 am today 🙂

The paper, and tasty cake, were the results of massive efforts by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Clement Kent, with the help of Shermineh Minaei and Brock Harpur (the latter two are recently minted MSc’s).

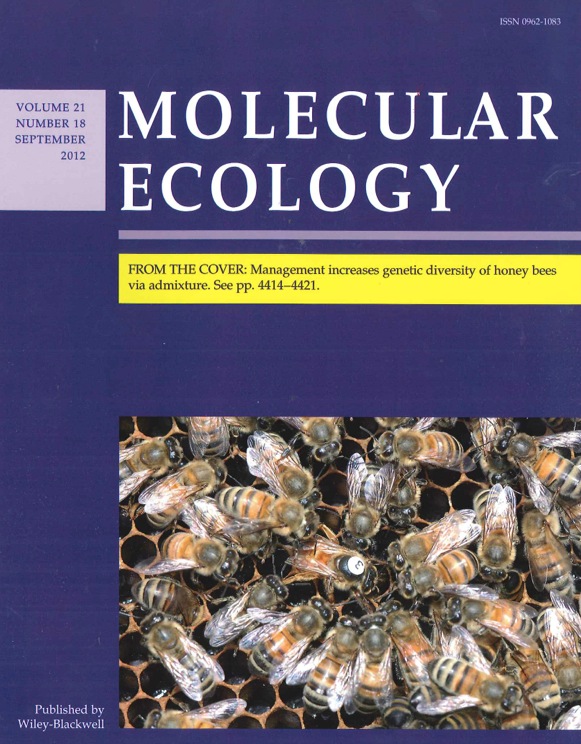

Diversity in honey bees: Cover and Perspective

Our paper on the effects of management on genetic diversity of honey bees appeared in print today in Molecular Ecology – we also got the cover picture (a nice picture of a queen with her retinue of workers). Also appearing in this issue is a very nice perspective on our research written by Dr. Ben Oldroyd from the University of Sydney Australia. Dr. Oldroyd has been studying honey bee genetics for more than two decades, and it is a honour to have him comment on our research.

The full citation of the perspective is:

OLDROYD, B. P. (2012), Domestication of honey bees was associated with expansion of genetic diversity. Molecular Ecology, 21: 4409–4411. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05641.x

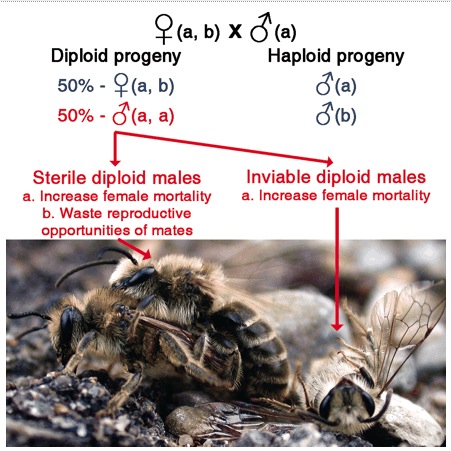

New Paper: Diploid males and female mating failures in ants, bees, and wasps

Happy to announce a new paper by the Zayed lab, just published by Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. The paper is an invited review on how the production of diploid males in ants/bees/wasps can cause female mating failures. It was authored by Brock Harpur (MSc candidate), and Mona Sobhani (undergraduate honours thesis student).

A mating between a male and female that share the same version of the sex-determining genes (here ‘a’). Half of the female’s fertilized eggs will be ‘a,a’ and will develop into diploid males. This is Fig. 1 from Zayed A, Packer L (2005) Complementary sex determination substantially increases extinction proneness of haplodiploid populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 10742-10746.

Sex in many ants, bees, and wasps is determined by the combination of alleles at one (but sometimes two or more) gene. Females arise from fertilized eggs and have two different ‘versions’ of the sex-determining gene. Normally, males arise from unfertilized eggs and only have a single ‘version’ of the sex determining gene; these are normal ‘haploid’ males. Sometimes – when there isn’t enough genetic diversity at the sex determining gene – zygotes can have two of the same ‘version’ of the sex-determining gene; this tricks the sex determination system into thinking that there is only one copy, and so a diploid male if produced.

For the paper, we reviewed the literature to learn more about the fate of these diploid males. We found that diploid males often reach adulthood, and are often capable of mating with females. However, diploid males in most species are effectively sterile and females mating with diploid males can not produce daughters of their own. Even when diploid males are fertile, their mates produce an inferior number of daughters when compared to haploid males.

This is bad news for bee conservation genetics because diploid males have a much greater negative effect on population persistence when they are effectively sterile! [see the 2005 Zayed & Packer PNAS paper on this].

New Paper: Management increases genetic diversity of honey bees

I happy to announce a recent article by the lab, which appeared this week in Molecular Ecology, on the effect of management on genetic diversity in the honey bee. [See Press Release]

The honey bee has a very long relationship with Humans – the Pharaohs of Egypt had pictures of honey pots and written documents describing honey trade. The long history of management would suggest that humans have left their fingerprints on honey bee genetics.

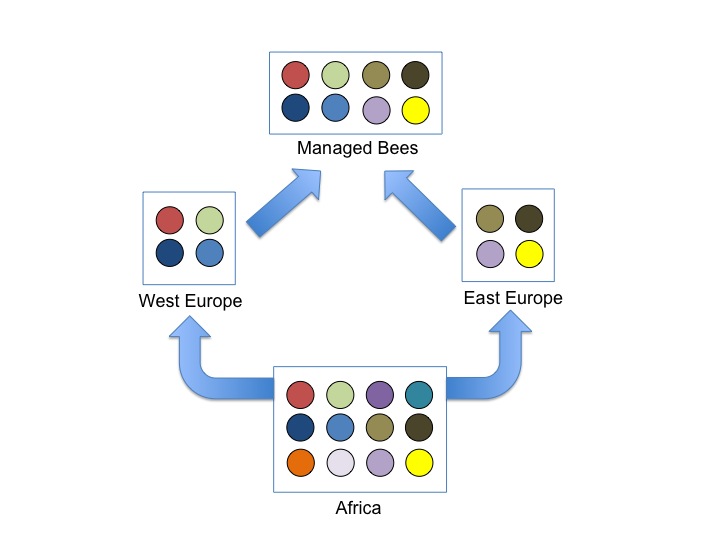

Cartoon showing the impact of out-of-African expansions on genetic diversity in Bees. We know that bees originated in Africa (most diverse population), then colonized Europe via two independent expansions; these expansions most likely involved a small number of individuals resulting in low genetic diversity in European subspecies. Human management encouraged interbreeding between these distinct European races which then elevated genetic diversity of managed bees.

Domesticated animals often have reduced genetic diversity relative to their ancestors, because humans often utilize only a small number of progenitors that are then interbred and selected to enhance specific traits. There is a growing concern that honey bees have reduced genetic diversity because of selective breeding by humans, and that this reduced diversity is contributing to the bee’s alarming global declines. This idea is supported by a few studies that showed that European honey bees have reduced genetic diversity relative to African honey bees; the former is believed to be more ‘domesticated’ while the latter is thought to be more ‘wild’. However, the 2006 discovery by Charlie Whitfield and Colleagues that honey bees originated in Africa then colonized Europe throws a wrench at this argument; European bees are expected to have reduced diversity relative to African honey bees simply because of the founder events associated with colonization, and this has nothing to do with management. Actually, we – humans – also evolved in Africa before colonizing the new world and Eurasian human populations have reduced genetic diversity relative to human populations in Africa.

Our team, led by Brock Harpur with the help of Shermineh Minaei, and Dr. Clement Kent decided to revisit this topic by sequencing fragments of 20 random genes from the bee’s genome in progenitor populations in Africa, East Europe, and West Europe, as well as two managed populations in Canada and France.

Fig. 2 from article. Managed honey bees have more diversity when compared with their progenitor populations in East and West Europe.

Just as we expected, we found that managed populations were mostly a mix of east and west European bees (beekeepers favour these bees for their productivity, cold-hardiness, and sometimes gentleness!). But west and east European bees are themselves a product of two independent out-of-Africa expansions; each have reduced diversity relative to Africa because of bottlenecks (a fancy term describing how genetic diversity is lost when only a small number of individuals are picked to start a new population; think of picking only a few M&M’s from a package – there is no way you can capture all of the differently coloured M&M’s from such a small sample).

By moving colonies and subspecies around, Humans brought together two groups of European bees that were naturally separated and distinct. Because Queen Bees naturally mate with 15-20 different males from nearby areas, the resulting managed populations became mixed. This mixing resulted in higher levels of genetic diversity in managed bees relative to progenitors in East and West Europe!

Congrats to Brock for his 1st-1st authored paper, and to Shermineh for her 1st publication.

New Paper: Drones are from Mars, Workers are from Venus!

I have a new paper out from a collaboration with Dr. Gene Robinson and his group at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. [see YorkU Press Release]

Honey bee societies are composed of three castes and two sexes. Female bees are either queens or workers; the queen bee lays all the eggs, while the workers do pretty much everything else (build the colony by secreting wax, heat and cool the colony, guard it from intruders, nurse and care for young larva, and collect pollen and nectar). Male bees on the other-hand, have a somewhat more privileged life – their entire existence involves finding virgin queens and mating with them! They are fed by workers, but they do not help out with the day to day activities needed to maintain the hive. This form of social organization represents a major transition in animal evolution. How and why do workers forgo reproduction to help their mom and brothers reproduce ?

We are not very far from answering this question. Both queens, workers and drones have the same genes, and some of the recent advances in the field have come from seeing which genes get turned on or off at different times during the bee’s development to give rise to the distinct castes of honey bees.

Queue-in the bee battle of the sexes! Worker bees and drones have some interesting similarities and differences. Drones and workers spend a period of time inside the hive, prior to initiating mating and foraging flights respectively. This transition from in-hive to out-hive activities are also ‘regulated’ by similar hormone and genetics in both drones and workers. For example, juvenile hormone increases the onset of mating and foraging in drones and workers respectively. Also, colonies where workers start foraging early have drones that start going on mating flights early. So it appears that maturation of drones and workers are under the common control of genes and physiology.

What then accounts for the big differences in behaviour between the two? Workers are much better learners (they take fewer risks!), navigators (they don’t get lost as easily!), and they are extremely sensitive to their environment (they can pace their maturation in tune with the queen and their sisters’ needs). The foragers also perform the ‘waggle dance’, which communicates information about the location and quality of food resources to their sisters.

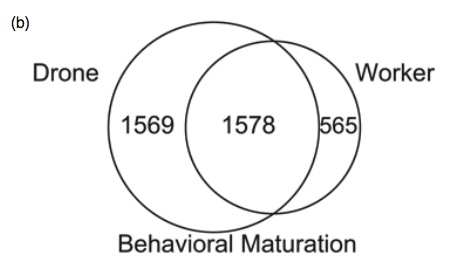

We set-out to study differences in the brains between drones and workers. We collected drones and workers at two time frames; when they are very young and are still in the hive, and after the onset of mating flights and foraging flights. We dissected the bees, and examined which genes are turned on or off in their brains. We found massive differences in the brain profiles of drones and workers (~ 40% of genes had sex-difference).

Venn diagram showing changes in brain gene profiles associated with maturation in workers and drones. From Zayed et al 2011

Many of the genes that showed sex-differences are known to play a role in behaviour, learning and memory in solitary critters like the lab mice and the fruit fly. But the interesting part was that most of the changes in brain profiles that we observed as workers matured were also present in drones. This suggests that the shift from nursing to foraging in workers was built upon an existing program for maturation in insects.

The study opens the door to understanding the genetic and molecular basis of worker behaviour, and how these social behaviours evolved.

Perspective on egg-yolk evolution paper

Dr. Gro Amdam’s group wrote a perspective to accompany the lab’s first article on the evolution of the egg yolk protein in the bee. We are very happy given that Dr. Amdam has literally written the egg yolk protein story for the honey bee over the past several years.

The full citation of the perspective is found below:

HAVUKAINEN, H., HALSKAU, Ø. and AMDAM, G. V. (2011), Social pleiotropy and the molecular evolution of honey bee vitellogenin. Molecular Ecology, 20: 5111–5113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05351.x

New Paper: Evolution of the egg-yolk protein in honey bees

I am very happy to announce the first paper from the Zayed lab, recently published by journal Molecular Ecology, on the evolution of the egg-yolk protein in honey bees. As the name implies, egg-yolk proteins are used to provision animal eggs with the necessary proteins and fats. The egg-yolk protein in honey bees is very interesting. Queen honey bees are egg laying machines; they have massive ovaries and can lay 1,000+ eggs per day! Queens make a lot of the egg-yolk protein to provision these eggs. But workers bees are effectively sterile, so they do not need to make egg-yorlk proteins, right? Well, as it turns out, worker bees also synthesize egg-yolk protein but use it in a different way. They use it to make food secretions which they spit out to feed younger bees. Also, the egg-yolk protein interacts with an important hormone in workers to affect the way workers behave. So, the egg-yolk protein affects both queen bee traits as well as worker bee traits. Now, imagine a new mutation in the egg-yolk protein… Can this mutation spread in honey bee populations given that the egg yolk protein is used differently in queens and workers? In other words, if a new mutation is good for the queen, is it also good (or neutral) for workers? If this is the case, then we should see lots of signs of positive selection on the egg-york protein. You can also imagine an alternative scenario – if a new mutation is good for workers but bad for queens (or vice versa), then we would expect the gene to show signs of ‘constraint’ – the protein is ‘stuck’ in evolutionary terms because it is being pulled in opposite directions by queens and workers.

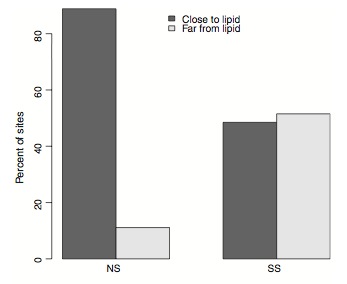

Egg yolk protein (Vg) adaptively evolves in the bee, Y>0 indicates positive selection; (reproduced from Kent et al 2011)

We decided to test this idea by sequencing the egg-yolk protein, along with seven other genes (controls) in honey bees from Africa and Europe. Two undergraduate Research At York students carried out the molecular biology work (Amer Issa and Alexandra Bunting, both co-authors on the paper), while NSERC Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Clement Kent carried out the population genetic analyses. We found very high levels of adaptive evolution acting on the egg-yolk protein, supporting the idea that what is good for the Queen is also good (or at least neutral) for Workers!

Dr. Kent cleverly mapped all the functional mutations to the egg-yolk protein’s 3D structure.

He found that almost all of them line the internal cavity of the egg-yolk protein where lipids are ‘bound’. This is very exciting as it suggest that mutations in the egg-yolk protein affect fitness in honey bees by changing the protein’s capacity to interact with lipids. We’ll be following up on this in future studies.

Functional mutations in the egg yolk protein are associated with lipid binding (reproduced from Kent et al 2011)

As it turns out, many genes in the honey bee genome are active in both workers and queens, and our work suggests that this may not constrain adaptation in the bee. From a practical point of view, our results show that the activation of genes in both queens and workers need not hinder breeding efforts. Beekeepers often breed colonies with good worker traits (e.g. good foraging, low aggression, good hygiene, etc.). Our study suggests that mutations which benefit one caste do not often disadvantage the other.