The lab will be featured on next Monday’s (7th Nov 2011) episode of “A Greener York” on RogersTV. I talked about how to help bees by planting pollinator gardens. The show is currently airing on TV and I’ll post the link to the online version once it is released.

Amro

Today was a fine day. We had a very important paper from the lab accepted in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), one of the top journals in our field. I can’t tell you much about the work for now – it is embargoed until officially published by the journal – other than… it is very very very cool! But, perhaps you can guess the topic after seeing our ‘PNAS Cake”! [feel free to send your guesses via the comment box below]

The cake-lady at highland farms had a good chuckle when i handed her fig. 2 of our manuscript at 8:45 am today 🙂

The paper, and tasty cake, were the results of massive efforts by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Clement Kent, with the help of Shermineh Minaei and Brock Harpur (the latter two are recently minted MSc’s).

L-R: Brock, Amro, Clement, Nadia, Tabashir, Arash, Anna

We had a very interesting queen in our last graft of the season; she had some damaged wings (problems with development? virus?). This is very bad, because virgin queens mate on the ‘wing’ !!! I was curious to see if the factors that affected her wing development also affected her reproductive abilities. So I instrumentally inseminated her with sperm from a single drone; half expecting that she will quickly overthrown by her workers. A month or so later, she is laying like a champ!

Also note the little primitively eusocial sweat bee Halictus confusus sneak into the honey bee cell while i was taking pictures of the queen – very cute!

Our paper on the effects of management on genetic diversity of honey bees appeared in print today in Molecular Ecology – we also got the cover picture (a nice picture of a queen with her retinue of workers). Also appearing in this issue is a very nice perspective on our research written by Dr. Ben Oldroyd from the University of Sydney Australia. Dr. Oldroyd has been studying honey bee genetics for more than two decades, and it is a honour to have him comment on our research.

The full citation of the perspective is:

OLDROYD, B. P. (2012), Domestication of honey bees was associated with expansion of genetic diversity. Molecular Ecology, 21: 4409–4411. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05641.x

My first cohort of grad students successfully fledged the nest last August – Brock and Shermineh both defended their Masters degree. Brock’s free time was incredibly short-lived, as he just started his PhD studies (on honey bee population genomics and health) last week!

Brock and Shermineh celebrate their shiny MSc degrees (note the gold stars!)

I also want to welcome Nadia – a new masters student in the lab. Nadia got to do serious bee work over the summer, where she figured out how to train honey bees to navigate through mazes! – very cool, check out this video! She’ll use this test to study the genetics of learning and memory in honey bees. Welcome Nadia!

Nadia; Only dedicated students inspect colonies in the rain with no gloves!!!

The lab also welcomes two Research at York Students; Anna and Jonathan, who will help us with some molecular biology and bioinformatics research respectively.

Fall Winter RAY’s:

Jonathan and Ann

We’ve been a very excited bunch this last month – we recently purchased a super fast computer server to crunch a very large dataset; the genomes of many worker bees.

Clement put in some serious efforts to get the server up and running… and man, does it ever run! The computer’s 24 cores crunch numbers so fast, that Amon had to wear a helmet when operating the machine!

Amon looks on as the server’s 24 cores light up (in red)

Clement, Amon, and Brock are in Awe!

Very happy to announce that Shermineh Minai successfully defend her Masters thesis today. Shermineh contributed greatly to the population and genetic evolution studies we undertook over the past two years. She was a co-author on the recent paper on the effects of management on genetic diversity in the honey bee, in addition to co-authoring a very exciting manuscript on the effects of recombination on GC content and molecular evolution in the honey bee (currently being reviewed). She also wrote another manuscript on the molecular evolution of transcription factors involved in regulating worker behaviour.

Congrats Shermineh on a very productive masters.

Amro

Congrats to Brock for successfully defending his masters’ thesis today. Brock’s thesis was awarded with distinction (top 5%) and contained one published paper and one manuscript that is about to be submitted. Brock was very productive; he completed one published side project and several other experiments that will be written up this fall/winter.

All you bee fans out there – don’t despair! Brock is continuing his research in the lab as a PhD candidate this September.

Congrats Brock!

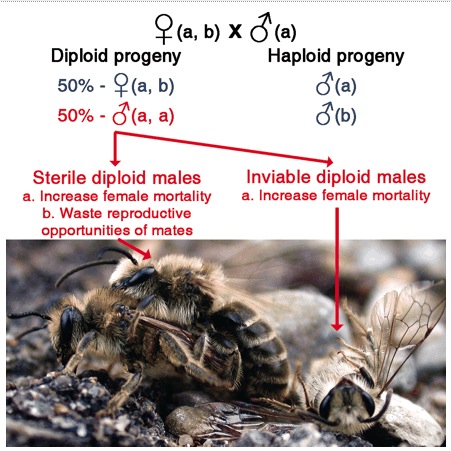

Happy to announce a new paper by the Zayed lab, just published by Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. The paper is an invited review on how the production of diploid males in ants/bees/wasps can cause female mating failures. It was authored by Brock Harpur (MSc candidate), and Mona Sobhani (undergraduate honours thesis student).

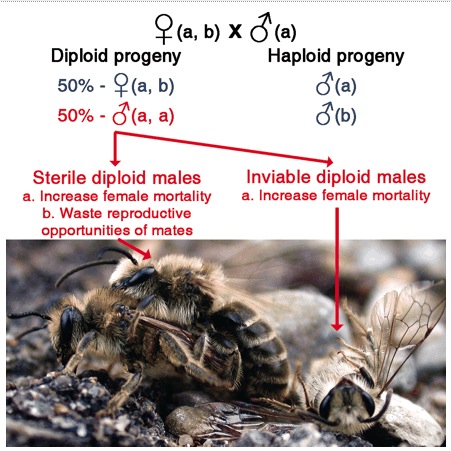

A mating between a male and female that share the same version of the sex-determining genes (here ‘a’). Half of the female’s fertilized eggs will be ‘a,a’ and will develop into diploid males. This is Fig. 1 from Zayed A, Packer L (2005) Complementary sex determination substantially increases extinction proneness of haplodiploid populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 10742-10746.

Sex in many ants, bees, and wasps is determined by the combination of alleles at one (but sometimes two or more) gene. Females arise from fertilized eggs and have two different ‘versions’ of the sex-determining gene. Normally, males arise from unfertilized eggs and only have a single ‘version’ of the sex determining gene; these are normal ‘haploid’ males. Sometimes – when there isn’t enough genetic diversity at the sex determining gene – zygotes can have two of the same ‘version’ of the sex-determining gene; this tricks the sex determination system into thinking that there is only one copy, and so a diploid male if produced.

For the paper, we reviewed the literature to learn more about the fate of these diploid males. We found that diploid males often reach adulthood, and are often capable of mating with females. However, diploid males in most species are effectively sterile and females mating with diploid males can not produce daughters of their own. Even when diploid males are fertile, their mates produce an inferior number of daughters when compared to haploid males.

This is bad news for bee conservation genetics because diploid males have a much greater negative effect on population persistence when they are effectively sterile! [see the 2005 Zayed & Packer PNAS paper on this].

I am happy to announce that we are hosting York’s latest spark student here at the lab. Spark is an award of up to $4000 allowing superstar high school students to participate in ground-breaking research at York University.

Amon will be joining our research group as we tackle studies of honey bee immunity and genomics.

Welcome Amon!

Check out Amon’s blog to learn more about his experiences in the honey bee lab!

(left to right: Brock, Clement, Nadia, Amon, Afshin)