New Paper: Management increases genetic diversity of honey bees

I happy to announce a recent article by the lab, which appeared this week in Molecular Ecology, on the effect of management on genetic diversity in the honey bee. [See Press Release]

The honey bee has a very long relationship with Humans – the Pharaohs of Egypt had pictures of honey pots and written documents describing honey trade. The long history of management would suggest that humans have left their fingerprints on honey bee genetics.

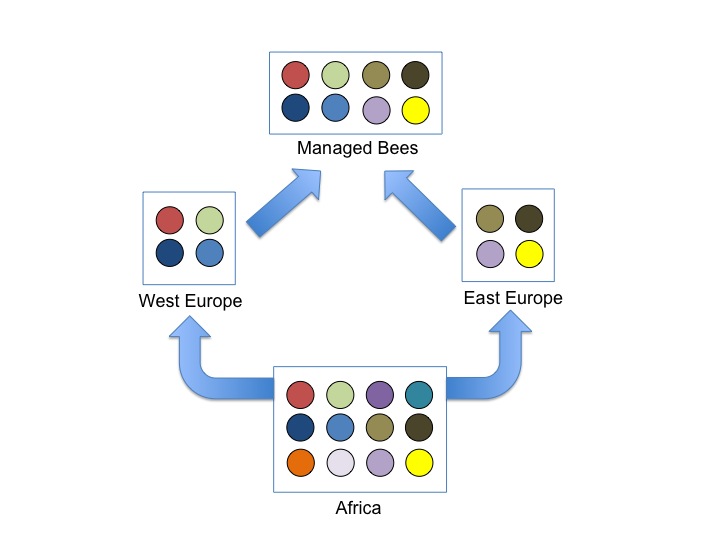

Cartoon showing the impact of out-of-African expansions on genetic diversity in Bees. We know that bees originated in Africa (most diverse population), then colonized Europe via two independent expansions; these expansions most likely involved a small number of individuals resulting in low genetic diversity in European subspecies. Human management encouraged interbreeding between these distinct European races which then elevated genetic diversity of managed bees.

Domesticated animals often have reduced genetic diversity relative to their ancestors, because humans often utilize only a small number of progenitors that are then interbred and selected to enhance specific traits. There is a growing concern that honey bees have reduced genetic diversity because of selective breeding by humans, and that this reduced diversity is contributing to the bee’s alarming global declines. This idea is supported by a few studies that showed that European honey bees have reduced genetic diversity relative to African honey bees; the former is believed to be more ‘domesticated’ while the latter is thought to be more ‘wild’. However, the 2006 discovery by Charlie Whitfield and Colleagues that honey bees originated in Africa then colonized Europe throws a wrench at this argument; European bees are expected to have reduced diversity relative to African honey bees simply because of the founder events associated with colonization, and this has nothing to do with management. Actually, we – humans – also evolved in Africa before colonizing the new world and Eurasian human populations have reduced genetic diversity relative to human populations in Africa.

Our team, led by Brock Harpur with the help of Shermineh Minaei, and Dr. Clement Kent decided to revisit this topic by sequencing fragments of 20 random genes from the bee’s genome in progenitor populations in Africa, East Europe, and West Europe, as well as two managed populations in Canada and France.

Fig. 2 from article. Managed honey bees have more diversity when compared with their progenitor populations in East and West Europe.

Just as we expected, we found that managed populations were mostly a mix of east and west European bees (beekeepers favour these bees for their productivity, cold-hardiness, and sometimes gentleness!). But west and east European bees are themselves a product of two independent out-of-Africa expansions; each have reduced diversity relative to Africa because of bottlenecks (a fancy term describing how genetic diversity is lost when only a small number of individuals are picked to start a new population; think of picking only a few M&M’s from a package – there is no way you can capture all of the differently coloured M&M’s from such a small sample).

By moving colonies and subspecies around, Humans brought together two groups of European bees that were naturally separated and distinct. Because Queen Bees naturally mate with 15-20 different males from nearby areas, the resulting managed populations became mixed. This mixing resulted in higher levels of genetic diversity in managed bees relative to progenitors in East and West Europe!

Congrats to Brock for his 1st-1st authored paper, and to Shermineh for her 1st publication.